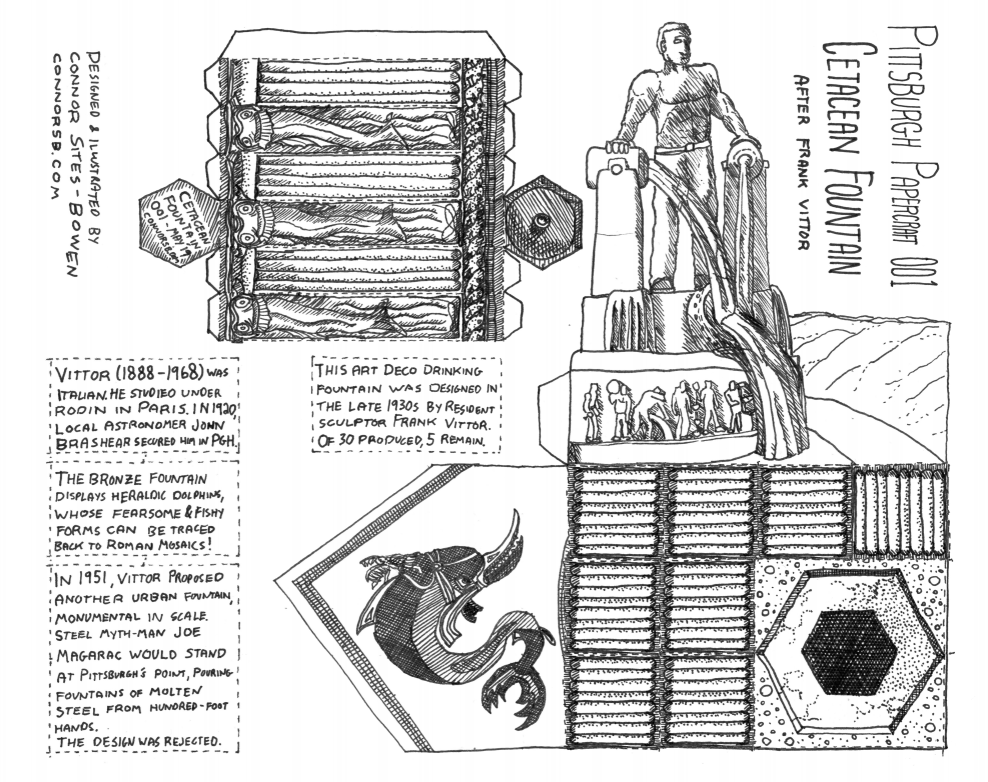

[The papercraft fountain, surrounded on the left and rear by its artistic inspiration, and the sculptor's planned monumental Joe Magarac fountain.]

My aim with this papercraft project was to produce an educational item about a piece of Pittsburgh’s past, suitable for sale at a museum shop or local-interest bookstore as a flat kit, which the user would cut and assemble at home.

Some specific design goals I had when I started:

Kit should be no more than two pages, and print on a standard laser printer (Single-sided US Letter).

Kit when assembled to its maximum should be a sort of miniature museum display, recreating the knowledge the museum houses on your shelf at home.

Final objects should be 1” grid-compatible, so that they can be reused for tabletop gaming as well.

I dove into Pittsburgh's built environment, looking for details, objects, and buildings which might be handsomely rendered in paper form.

The Historical Fountain

The object that I was drawn to was a drinking fountain, a beautiful bronze fountain in Highland Park, with strange fishlike creatures swirling down its watery art-deco sides.

Here’s how I described the fountain in my newsletter:

My first Pittsburgh Papercraft subject is a rare one - one of the five art deco drinking fountains to be found in the city's public parks. The most prominent one is at Highland Park, just to the left of the grand entrance. The fountains were crafted by Italian-born sculptor Frank Vittor, who moved to Pittsburgh when he became friends with local astronomer John Brashear. They depict fearsome heraldic dolphins, modeled on Roman artistic renderings of the fishlike mammals.

Mr. Vittor went on the have a long career of public art in Pittsburgh, from sculptures to relief murals to park infrastructure.

In the 1930s, resident sculptor Frank Vittor designed this art deco drinking fountain for installation across Pittsburgh’s urban parks. Thirty fountains were cast, of which five remain.

The fountains provided water to passers-by, and are each guarded by heraldic dolphins. The scaly, toothsome design of these dolphins can be traced back to Roman mosaics of the cetaceans as heralds and steeds of Eros (later called Cupid), the god of Love.

Vittor, who was born in Italy and trained as a sculptor and artist under Rodin in Paris, moved to Pittsburgh in 1920, after a 1917 visit where he met long term friend and local astronomer John Brashear. His works can be seen across the city, from the Boulevard of the Allies to the Westinghouse Bridge.

In 1951, he proposed a monumental sculpture at the Point - a hundred foot tall statue of the mythical steel-worker Joe Magarac. The larger-than-life worker would pour back-lit water (‘molten steel’) from full-sized ladles held in his bare hands, melding together and mimicking the confluence of the rivers.

The sculpture proposal was declined. Vittor continued to produce sculpture until his death in 1968.

Designing the Papercraft

First design decision: the scale of the various objects in the scene.

The snap-to-grid design requirement limited the fountain object’s diameter to either 1” or 2”. Tracing out the triangles within a hexagon within a square, I found that each hex-side must be .5” or 1” wide, respectively. From that math, it was clear that a six sided object at the larger scale would take up most of a page all by itself, while the smaller scale one would leave plenty of room for an entire containing environment in an L-shape around it. This economy of page-use appealed to me, and a fast mockup of the shapes felt good to hold and construct, so I went with the smaller scale: .5” sides, a 1” diameter, and a 3” final height for the fountain.

Second design decision: layout.

The L-shape left by the fountain can be folded upwards to create three faces of a rectangular prism, a corner of printed information, art, and diagrams, to give the dolphin fountain greater context.

(The displayed context information: the history of dolphin depiction in mythical art, and the sculptor’s later project proposal of a monumental civic statue of a steelworker’s heroically strong form. The former is a more universal topic in art - you find dolphins represented in art across thirty centuries, or more. The latter is a deep dive into alternate Pittsburgh histories - landmarks that never were, but were, at one time, proposed!)

The fountain’s top and bottom make its flattened form taller than it is wide, so the L shape has a corresponding composition to its two legs - one is much taller than the other. I used this taller side to depict the monumental sculpture, and the shorter one for the historical mosaic.

(please do not piratically download and print this low rez version. There is a paper kit available for sale here.)

Research Notes & Further Reading

If you’d like to learn more about the confluence of ideas these cetacean statues embody, here follows a few good places to start reading:

From 2008, this Post-Gazette article on the occasion of a historical sign dedication near the Columbus statue Vittor sculpted, near the Phipps Conservatory and Flagstaff Hill. The article goes into detail about many aspects of Vittor’s life. Some of the strangest details concern his arrival in Pittsburgh, precipitated in part by the famed beauty of young Evelyn Nesbit and the so-called “Crime of the Century”.

Many immigrants to the United States furnished labor for booming steel mills and coal mines. But Mr. Vittor was born into a family of artists in Mazzate, Como, a suburb of Milan, and began sculpting at the age of 9 when he made a wood carving in bas-relief of the poet Dante.

He was educated at the Brera Academy in Milan, then studied with Auguste Rodin in Paris. He came to America in 1906 as a protege of Stanford White, the famed New York architect.

But by the time Mr. Vittor arrived in New York, Stanford White had been shot dead by the jealous [over Ms. Nesbit] Harry K. Thaw in Madison Square Garden.

Despite his lack of money and knowledge of English, Mr. Vittor set up a New York studio. He later left Manhattan at the urging of the noted astronomer Dr. John A. Brashear, who saw five of Mr. Vittor's bronzes at a Pittsburgh gallery. Love played its part, too -- in 1917 he met and married a Pittsburgh woman named Adda Mae Humphreys and eventually set up a studio at 2565 Fifth Ave. in Oakland.

(Marker to honor 'sculptor of presidents' Frank Vittor Marylynne Pitz, Pittsburgh Post Gazette October 12, 2008.)

In January of 2016, Pittsburgh Magazine’s PittGirl explored a long history of proposals for the Point, none of which were built. She was able to find an old (but unnamed) Post-Gazette article, with the following description of the statue as completed:

Each arm of the massive figure would rest on upturned steel ladles, which, in turn, would pour simulated streams of molten steel into a third ladle. That typifies the joining of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers to form the Ohio.

Around the base of the statue, Vittor proposes that 40 10-to-12 foot figures be carved to show how production of steel in Pittsburgh affects the cultural, social and business life of the city.

On the outer rim of the statue, Vittor has designed a system of water fountains. They would draw water from both the Mon and Allegheny and project it into 50 to 100-foot streams around the statue.

The whole monument would be lighted at night, giving color to the water. The molten metal streams would glow, day and night.

Beneath the statue, Vittor has designed a room, at least 100 by 70 feet, to serve as a museum, aquarium, or industrial display space.

A short entry in the Father Pitt blog, with a few photos of the statues in 2009.

The Western Pennsylvania Numismatic Society has a thorough history of Mr. Vittor’s coin-work (the Gettysburg Half-Dollar) as well as many of his public statuary.

In 2012, the Post Gazette recorded an effort to cast more fountains, using the original molds, but after the City Council allocation approval, there isn’t much in the papers about how the project went.

![[The papercraft fountain, surrounded on the left and rear by its artistic inspiration, and the sculptor's planned monumental Joe Magarac fountain.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55058cc9e4b07d289193ebb1/1564502018226-AA254Q74E7SWNYFJ2WAD/20190512_122449.jpg)